Reflect on your Experience and Teaching

When the Black Lives Matter movement comes up in conversation, it is often characterized in one of two ways: as the work of strategic activists drawing attention to and combating issues that harm black people, black communities and humanity at large, or as a movement marked by violent outbursts and driven by an exclusionary, racist, anti-police agenda.

This split gives some educators pause when it comes to teaching about BLM. Others embrace the topic, recognizing it as an opportunity to teach about collective action and to link past racial justice movements to the present. But all educators, by virtue of the fact that their students have either direct or mediated exposure to Black Lives Matter, should know the basic facts about the movement’s central beliefs and practices.

Not all of us are like Thompson; the students who sit in front of us daily are not always directly affected by the killing of unarmed black people or any of the other injustices that plague our nation. But as teachers who function as caretakers, truth-seekers and advocates of justice, we can acknowledge how the threat of justice in one community is, to borrow from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a threat to justice in every community. We have a civic responsibility to be educated about Black Lives Matter and, as we learn, we must teach. (Pitts, 2017)

Teaching about BLM isn’t just about police brutality and the ways an organization is seeking to end it. Bringing this movement to the classroom can open the door to larger conversations about truth, justice, activism, healing and reconciliation.

The work required to teach about Black Lives Matter is extensive and heavy, but this topic can be addressed effectively in classrooms—at any grade level. (Pitts, 2017)

Black Lives Matter at School Resource Toolkit (Recognized February 17th)

As educators, we need to have courageous, honest dialogues about race, and about what is happening in our society and in our students’ lives. Building strong relationships with students and colleagues is a critical component of our work to know “Every Student By Face and Name. Every School, Every Classroom. To and Through Graduation.” This document is intended to provide you with resources to use in preparing to participate in this day of affirmation. Thank you for partnering with us in this work to improve the Rochester community.

Why do those who counter black lives matter act as though black people aren't aware of the glaring disproportionate statistics of police brutality, of health care racism, and of mass incarceration? This is our reality. You deciding to ignore it for your own comfort doesn't make it any less true.

If a patient being rushed to the ER after an accident were to point to their mangled leg and say, “This is what matters right now,” and the doctor saw the scrapes and bruises of other areas and countered, “but all of you matters,” wouldn’t there be a question as to why he doesn't show urgency in aiding that what is most at risk?

The committee drafted and presented a resolution before the Rochester Teachers Association’s Representative Assembly. The resolution states, “[S]chools should be places for the practice of equity, for the building of understanding, and for the active engagement of all in creating pathways to freedom and justice for all people.” It passed unanimously, with the association endorsing and encouraging district teachers to participate in a “day of understanding” that affirms that black lives matter at school.

Shortly thereafter, the Rochester Board of Education and Association of Supervisors and Administrators of Rochester voted to adopt similar resolutions, making “Black Lives Matter at School” an official initiative of the district.

In a letter to all staff, the district superintendent and senior district leaders articulated the vision for the day: “Through our collective participation … students will learn that their school district: understands inequities based on race; affirms that the lives of people of color matter; believes that we all have a responsibility to work for equity.” (Lindberg, 2017)

In support of the Movement for Black Lives, we share this collection of teaching ideas and resources. The Movement for Black Lives challenges the ongoing murders of African Americans by the police and the long history of institutionalized racism. This resource collection was originally published in August of 2014, after the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. See additional resources compiled for the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action. Updated February 2018.

“I think the pedagogy in the classroom is important, but it rings hollow if you’re telling your kids, ‘Here are the great movements for social and racial justice’ and engaging them in those conversations, but then not doing it yourself in your own life,” Hagopian says. “I think it’s incumbent upon social justice educators who are teaching this stuff to also live it, and that means getting involved with the Black Lives Matter at School movement, to get involved with the movements for structural change. (Dillard, 2019)

More than a quarter of the 1,217 arrests in Indiana schools in 2018-19 were of Black students, even though they only made up 14% of the state’s student population, raising questions of racial bias and educational inequity.

The consequences can be dire: Students who are arrested are less likely to graduate or succeed academically and more likely to be involved with the criminal justice system in the future, research has found. (Wang & McCoy, 2020)

Challenge implicit biases by identifying your own, teaching colleagues about them, observing gap-closing teachers, stopping "tone policing," and tuning into such biases at your school. (Safir, 2016)

Anti-bias curriculum is an approach to early childhood education that sets forth values-based principles and methodology in support of respecting and embracing differences and acting against bias and unfairness. Anti-bias teaching requires critical thinking and problem solving by both children and adults. The overarching goal is creating a climate of positive self and group identity development, through which every child will achieve her or his fullest potential.

The book, Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves, by Louise Derman-Sparks and Julie Olsen Edwards, offers practical guidance to early childhood educators (including parents) for confronting and eliminating barriers of prejudice, misinformation, and bias about specific aspects of personal and social identity; most importantly, it includes tips for adults and children to respect each other, themselves, and all people. Below you will find recommended books for young children, teachers, and parents for each chapter as well as additional resources on anti-bias themes and topics.

The first step in overcoming implicit bias is to identify and acknowledge the bias. The next step is to stop the bias while it is occurring. The third step is taking action to change the bias. Studies have shown that we all have implicit bias as it is part of our subconscious and everyday life. We need to acknowledge that bias in ourselves through self-awareness. Next, we need to question ourselves when one of our own stereotypes manifests itself and replace it by asking ourselves to look at the situational circumstances that could have impacted a person's behavior rather than our stereotype that we hold. We need to change our prejudiced habits by asking questions and engaging with others who are different from us.

Explicit bias underlies the troubling conclusion from TNTP’s Opportunity Myth report that “classrooms that served predominantly students from higher-income backgrounds spent twice as much time on grade-appropriate assignments and five times as much time with strong instruction, compared to classrooms with predominantly students from low-income backgrounds.”

These aren’t some deep-down inside, subconscious, “I had no idea what was doing” beliefs. These are actual actions of explicit bias that occur every day and carry far more drastic consequences than the occasional viral picture or Facebook post of racist teachers. And these every day actions of explicit bias are equally, if not more deserving of our outrage because these have real consequences for our children. (Seale, 2019)

1. Cultivate awareness of their biases

2. Work to increase empathy and empathic communication

3. Practice mindfulness and loving-kindness

4. Develop cross-group friendships in their own lives

Listen as Dr. CI breaks down the difference between implicit bias vs. explicit bias!

Implicit bias is something that is unconscious- you don’t know you are doing it. An explicit bias is a conscious bias you are aware of. There is a difference- an implicit bias can transfer to an explicit bias when you consciously aware of your prejudice.

“These types of cultural biases are like smog in the air,” Jennifer Richeson, a Yale psychologist, wrote in an email, citing an analogy often used by a former president of Spelman College, Beverly Daniel Tatum. “To live and grow up in our culture, then, is to ‘take in’ these cultural messages and biases and do so largely unconsciously.”

In the context of race, implicit bias is considered a particularly important idea because it acknowledges forces beyond bigotry that perpetuate inequality. If we talk less about it, as Mr. Pence suggested — this “really has got to stop,” he said Tuesday night — we lose vocabulary that allows us to confront racial disparities without focusing on the character of individual people. (Badger, 2016)

“These types of cultural biases are like smog in the air,” Jennifer Richeson, a Yale psychologist, wrote in an email, citing an analogy often used by a former president of Spelman College, Beverly Daniel Tatum. “To live and grow up in our culture, then, is to ‘take in’ these cultural messages and biases and do so largely unconsciously.”

In the context of race, implicit bias is considered a particularly important idea because it acknowledges forces beyond bigotry that perpetuate inequality. If we talk less about it, as Mr. Pence suggested — this “really has got to stop,” he said Tuesday night — we lose vocabulary that allows us to confront racial disparities without focusing on the character of individual people. (Badger, 2016)

Stories

Neil deGrasse Tyson was asked: Why aren't there more women in science? |

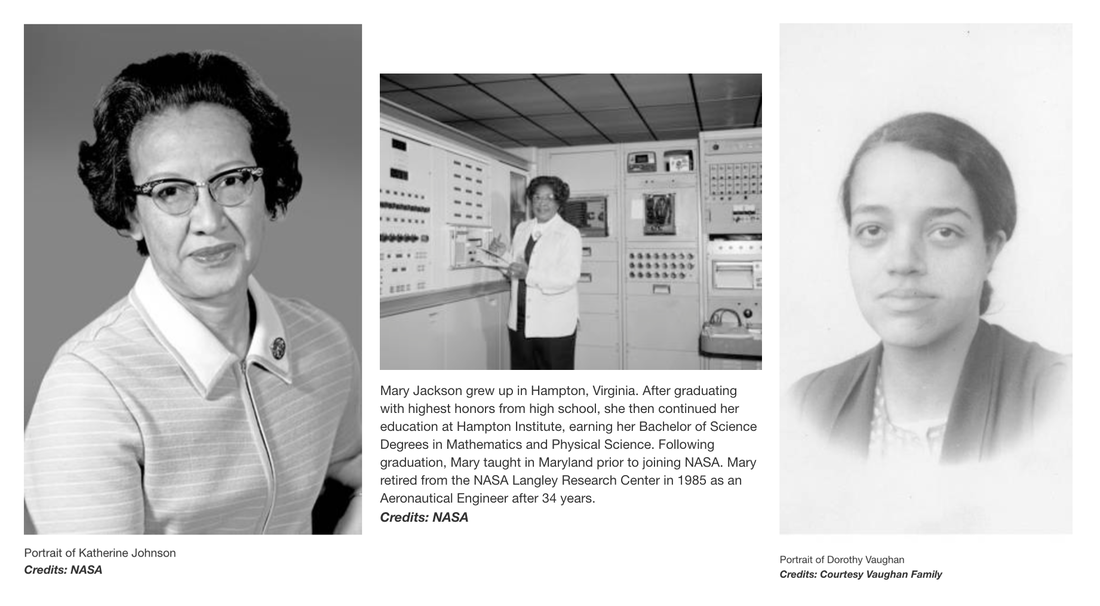

The film "Hidden Figures," based on the book by Margot Lee Shetterly, focuses on Katherine Johnson (left), Mary Jackson and Dorothy Vaughan, African-American women who were essential to the success of early spaceflight. NASA embraces their legacy and strives to include everyone who wants to participate in ongoing exploration. |

In the following excerpt from the 2019 collection Democratic Discord in Schools: Cases and Commentaries in Educational Ethics, Clint Smith responds to a case study titled “Bending Toward—or Away From—Racial Justice?” The study follows an instructional support specialist tasked with implementing a new, culturally responsive curriculum. The specialist faces challenges from families demonstrating white fragility and educators unwilling or unprepared to teach the new lessons.

Dr. Joshua Schuschke will discuss “Expectations, Opportunities, and Futures: Culturally Responsive Learning Environments for Black Girls in the Digital Age” Bring your lunch and join us!

This session focuses on antiracist and culturally responsive strategies that the audience can utilize in learning environments. Presenters: Dr. Jenice View (George Mason University) and Dr. Meredith Anderson (United Negro College Fund). Facilitated by Dr. Samantha Cohen, Director of AU EdD Program.

Black and Latinx girls need anti-racist, culturally responsive learning environments. They need the support of relatives and of mentors — especially teachers — who look like them. And they need to not be punished for speaking up about their beliefs and opinions.

First, culturally relevant and rigorous curriculum. Second, students experience belonging as scholars in the intellectual community of school. Third, students experience a socially-emotionally and intellectually safe learning environment. Last, listen to students. (Gonzales, 2020)

It’s a time-honored school tradition—a day of food and fun celebrating all the cultures represented at your school. Mexican folkloric dance! Korean hanbok fashion show! Spanikopita taste-testing! Unfortunately, however well-intentioned, Culture Day is a misguided effort. And, as you’ll see, these events often have the opposite of their intended effect.

I say all this acknowledging that I’ve participated in plenty of culture fairs at school. I’ve staffed booths at PTA events for countries I’ve visited (*cringes*). I even orchestrated an entire Amazing Race where students experienced music, food, and holidays from around the world. (Fink, 2020)

When Black students exhibit negative behaviors or become withdrawn, educators often label them as problems and subject them to reactionary, zero-tolerance policies and other practices that disproportionately affect Black students but don’t address the root causes of such behavior.

This harm manifests in a number of ways: adopting curriculum that isn’t culturally responsive, lowering academic expectations, tracking Black students into remedial or special education classes and seeing Black youth as older and less innocent than their white peers—a bias known as adultification. (Dillard, 2019)

The content of these conversations feel eerily similar to some of education’s favorite social-emotional learning (SEL) slogans: mindfulness, resilience and grit. Mindfulness implores students to remain calm, and take 10 deep breaths when they feel themselves getting angry. Resilience encourages students to hold their heads high despite mistreatment. Grit tells students to persevere in the face of obstacles.

Some educators believe that mastery of these traits can guarantee a student’s success. But what they overlook is something that every Black parent is painfully aware of: A Black child can do every single one of these things perfectly, and still not make it home. (Weaver, 2020)

The ‘educating the whole child’ mantra floats around many districts and is common in reports such as this one by The Learning Policy Institute. I 100% agree with the philosophy of holistic development but have found that culture is seldom central and fundamental to this body of work. Given that most educators and mental health professionals are White and too few have extensive formal preparation in equity, diversity, and inclusion, I am not surprised by the void, but I am disappointed and alarmed. I am concerned for Black students who need SEL guidance (Ford, 2020).

Having a multicultural perspective requires SEL skills, and neither can be conveyed didactically. Both the perspective and skills become developed through guided, lived experience, even in schools that may appear to be lacking diversity -- at least on the surface.

When it comes to developing students' multicultural perspective, what are your thoughts and ideas?

In addition, many popular SEL approaches do not explicitly confront these forms of violence or other social inequities. Recoiling from topics that divide us—when SEL skills could help us get along better—diminishes SEL's promise. Why teach relationship skills if the lessons do not reflect on the interpersonal conflicts that result from racism? Why discuss self- and social awareness without considering power and privilege, even if that means examining controversial topics like white supremacy?

Maintaining a safe space that prevents triggering students is crucially important when infusing SEL opportunities with the sociopolitical context. (Simmons, 2019)

Healing, for Black and Brown young people, should be centered in SEL. We must not lose the importance of co-constructing spaces with young people to lean into creative expression and joy — to shift conversations to what Dr. Shawn Ginwright calls a healing-centered perspective, where young people are reminded that they are not just their trauma, but rather all of the ways they continue to dream, imagine, hope, and grow. Let them dance, sing, laugh, play, scream, organize, and encourage all the brilliant ways they show up. SEL devoid of culturally-affirming practices and understandings is not SEL at all.

“One can agree that education is a great human equalizer, yet there are still schools that have significantly fewer resources and less funding than others. There are still many students, predominantly Black and Brown, who are stereotyped as "below standard" before they are loved, taught, and respected. Teachers are still underpaid and overworked, often blamed for all of the failings of the public education system. However, the problems of the public education system are layered and connected to policymakers, school districts, parents, teachers, students, and deeply entrenched racist ideologies. A surefire way to penetrate the racialized and class-based problems of urban school systems is by adopting a social justice pedagogy.” (Belle, 2019).

A common myth regarding multicultural education is that it is about helping students of color see themselves within the content. But multicultural education is about more than just race: It refers to any form of learning or teaching that incorporates the histories, texts, values, beliefs, and perspectives of people from different cultural backgrounds (Glossary of Education Reform). And even if the majority of your students are White, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t teach from a multicultural perspective. (Eakins, 2020)

We have to create an environment where they are unafraid to take risks, where they believe that they can be anything. We have to have high expectations. We have to show them that we believe in their ability to be successful. We show them these things through rigorous work tasks and support—if we give them a task, we must show them how to do it. We need to show them that they are loved. We need to show them that they have power.

Real change, social justice and the school-to-activism pipeline start in our classrooms. If we want to change the world, we have to start with ourselves and then with our students. Tupac Shakur said, “I’m not saying I am going to change the world, but I guarantee that I will spark the brain that will change the world.” We have that power, educators. We might not change the whole world, but if we just spark the mind of one child in our classroom, we can make a difference. (Wing, 2019)

Here are examples of guiding questions we share with students who are examining books (text and illustrations) in their home or school libraries. We use these same questions (and many more) when developing the book lists and selecting book reviews for this website.

- How many books by or about people of color and Native Americans do you see?

- Does this reflect the diversity that you see in your school, community, and/or the world?

- Are people of color engaged in a range of activities and in contemporary settings? (Or just in historic injustices?)

- If the books are about a famous person, is it someone you have not heard of or one of the same few people already on your bookshelf?

- Is change made by an individual hero or a group effort?

- Are there examples of “ordinary” people organizing and challenging injustice?

- Are the root causes of inequities included or just the symptoms?

- Are the books affirming, honest, age-appropriate, and read-me-again interesting?

- What is the relationship of the author to the people and theme of the book?

Dr. Brian McGowan sits down with Dr. Connie Jones, Dr. Katrina Overby, Dr. J.T. Snipes, and Dr. LaWanda Ward to discuss Social Justice in Higher Education.

Successful social justice projects require raising students’ awareness about issues and providing advocacy and aid opportunities.

“As educators, we’re charged with preparing our students to be successful in life and to be productive members of society. But with all the focus on standardized tests and core curriculum, we’ve forgotten that the concept of literacy should also include culture and tolerance of diverse people and backgrounds.” (Hernandez, 2016)

Use young children’s understanding of differences to teach social justice through age-appropriate literature, news stories, anti-bias lessons, familiar examples, and problem solving (Spiegler, 2016)

The Social Justice Standards are a set of anchor standards and age-appropriate learning outcomes divided into four domains—identity, diversity, justice and action (IDJA). The standards provide a common language and organizational structure: Teachers can use them to guide curriculum development, and administrators can use them to make schools more just, equitable and safe. The standards are leveled for every stage of K–12 education and include school-based scenarios to show what anti-bias attitudes and behavior may look like in the classroom.

Teaching about IDJA allows educators to engage a range of anti-bias, multicultural and social justice issues. This continuum of engagement is unique among social justice teaching materials, which tend to focus on one of two areas: either reducing prejudice or advocating collective action. Prejudice reduction seeks to minimize conflict and generally focuses on changing the attitudes and behaviors of a dominant group. Collective action challenges inequality directly by raising consciousness and focusing on improving conditions for under-represented groups. The standards recognize that, in today’s diverse classrooms, students need knowledge and skills related to both prejudice reduction and collective action.

The Social Justice Standards support the Perspectives for a Diverse America K–12 curriculum. For more information about Perspectives, visit perspectives.tolerance.org.

An interview featuring Erin Maguire director of equity, diversity and inclusion at the Essex Westford School District and Christie Nold, a social studies teacher at Frederick H. Tuttle Middle School in South Burlington. Both provide essential insight to this work and invite educators (from all backgrounds) to reflect on the systems we have in place and how that affects the learning of our students.

One of the biggest hurdles when talking to white parents about race, especially as a Black nanny or babysitter, is addressing the myth that race isn’t something they need to acknowledge with their children. “A lot of white parents are steeped in colorblind ideology, and they really think their kid doesn’t notice race,” Pahlke explains.

When faced with these conversations, it’s important to stress to the parents that children asking about racial differences is not necessarily a reflection on poor parenting, but rather a very normal part of a child’s development. Kids notice race, whether parents talk to them about it or not. (Shabazz, 2020)

The goal in teaching about race and racism is certainly not to whitewash the history of racial terror in this country, but to offer a more complex narrative in which White students can see a different way forward other than being either silent or oppressive, and Students of Color can see themselves outside of the relentless stereotypes that continue to pervade the curricula in U.S. education. It is not an either/or world. So we need to stop offering students simplistic and inaccurate versions of history and racial identity, often relying on myths and stereotypes as the frame for conversations on race in school. We need teachers, in other words, to develop more critical and accurate narratives, nuanced portraits that embrace racial identity and challenge racism. (Mills, Chandler, & Denevi, 2020).

Teachers cannot go about their work thinking their classrooms are beacons of justice and antiracism without fully understanding the system students are up against. (Wright, 2020)

The purpose of education, finally, is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions, to say to himself this is black or this is white, to decide for himself whether there is a God in heaven or not. To ask questions of the universe, and then learn to live with those questions, is the way he achieves his own identity. (Baldwin, 1963)

Too often, African-American students will show frustration and an understandable sense of heaviness when learning about their history, since the narratives that teachers provide are frequently centered around slavery and oppression. These lopsided classroom and societal narratives create inaccurate and imbalanced notions of black identities. By not discussing African Americans of the past with the full range of human experience in mind-never teaching the triumphs with the trials-these narratives feed this perpetual lie of white superiority that we should be working hard to break with our teaching.

While oppression is part of black history and black present, it is imperative that teachers don't make that the whole story. It is not OK to skip over the innumerable contributions of African Americans to the United States. Black children also need to engage with images and narratives of their people and ancestors as survivors, revolutionaries, artists, scientists, creators, musicians, dancers, astronauts, politicians and pioneers. All students need to engage with black history in this way. (Pitts, 2020)

In partnership with Education Post, the Campaign for Black Male Achievement (CBMA) has launched the Black Male Educators Speak video series, focusing on the stories of four Black male teachers in four different cities and exploring the innovative teaching methods they use to engage Black students.

But there’s more at stake than the educational benefits of having black teachers for black students. Ultimately, all students benefit from teachers of color, as exposure to individuals from all walks of life can reduce stereotypes, prevent unconscious bias, and prepare students to succeed in a diverse society.

When high-profile incidents of racial hatred occur — as in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, when nine people were shot and killed during Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, and in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, when an alt-right march precipitated the death of an antiracist protester — there is a tendency to circumscribe white supremacy and racism to their most extreme and explosive forms. However, we should not let racism at its most violent distract us from the mundane practices and quiet systems that can help foster notions of white superiority. So I’ll say it again: Representation matters. Not seeing qualified, competent black folk in positions of authority may reinforce the belief, conscious or unconscious, that black people are less worthy in some way than white people. And practices that push black people out of very visible jobs, such as teaching, are harmful to society as a whole. I often say that losing black teachers is proof of the slow leak of democracy. (Perry, 2019)

Teach students that every act against bigotry, no matter how big or small, is powerful. Stop ignoring the prejudiced commentaries at your own dinner table. Stop looking the other way when people in your network make underhanded, thinly-veiled bigoted comments and call out the behavior. We all have a responsibility to stop everyday bias when we #Teach4Maud. As an educator, do the necessary work of examining your own bias and seek to weed out those areas of bias in your life. (Wing, 2020)

Moreover, the silence on the part of white teachers who teach black and brown children is insulting. Imagine seeing white people, the perceived dominant race, loving and appreciating black culture when it is pretty—enjoying the music, food, culture and beauty of our people—but remaining silent about our oppression and refusing to see how the beauty of our culture was largely born out of necessity. It hurts students when their teachers only acknowledge what black people have done for this country and not what this country has done to them.

But how encouraging is it to know that we stand in a powerful and political position where we can directly influence and break this silence?

Begin by confronting your own biases—about yourself, your students, your fellow educators, the world. This process is essential; if educators don’t do this, think about how much damage we could do to the open, vulnerable minds of our students. In particular, examine your feelings about the police. And, regardless of your personal feelings about law enforcement, it is critical to understand that many black and brown students have incredibly negative perceptions about the police. This difficult understanding on the part of teachers can hopefully lead to dialogue and healing in schools. (Pitts, 2016)

Zero tolerance and other exclusionary school discipline policies are pushing kids out of the classroom and into the criminal justice system at unprecedented rates. Too many students are lost to our communities this way. Disciplined at disproportionate rates and with heightened severity for minor infractions that used to warrant a trip to the principal’s office, students of color are most impacted.

This is a guest lesson from Jinnie Spiegler, the director of curriculum at the Anti-Defamation League. She has written for us previously on 10 Ways to Talk to Students About Sensitive Issues in the News.

You might choose to use this lesson with our related Student Opinion question, “Why is race so hard to talk about?” (Spiegler, 2017)

If you let them tell it, Black kids are in terrible shape while White children are doing gloriously. But how can White kids be doing okay when they’re growing up to be police officers, district attorneys, mayors, judges, media, mothers, fathers and presidents who take away Black life and call it justified? As Black bodies drop like flies around us from physical, medical, economic, and material deprivation and violence at White hands, how can we in any of our minds or metrics conclude that the Whites are alright? What kind of warped standards are these?

Because let me tell you something …

- A child who grows up to put their knee on someone’s neck and kill them in front of a crowd is “culturally deprived.”

A child who jumps in a car with their parent and chases down and executes a stranger is a “super predator."

A child who grows up to shoot people while they are worshipping is “at-risk.”

A child who can grow up and never be confronted with how they benefit from racist violence is “levels behind”. (Webber, 2020)

As educators, you can either empower or oppress students by the way you choose to teach and see them. Your intentional decisions to incorporate some communities and identities into the classroom while leaving others out show which side you choose.

The absence of education that incorporated various identities—and my subsequent, subconscious acceptance of others’ mistreatment of my intersectionality—shows me that the educators in my life chose to oppress.

Since the early 1990s, scholars have studied mixed-race and multiracial identity development among college students. While more work needs to be done in this area, researchers continue to grapple with how mixed-race and multiracial students experience higher education. Some have sought to understand mixed and multiracial students’ level of engagement across and within different institutional types.

This work is important because navigating higher education as a mixed or multiracial student comes with unique challenges in areas such as the admissions process, campus life and co-curricular involvement. Some mixed and multiracial students struggle with answering questions about race during the college admissions process and express concerns about the implications for identifying or not identifying with certain racial backgrounds. (Barone, 2018)

This framing also furthers the fiction that when women, first-generation students, low-income students, students with disabilities, transgender students and so forth are in the classroom, faculty members must put aside identity-neutral content and attend to identity. The reality, however, is that all students benefit when a multiplicity of identities are reflected in the classroom, whether in the curriculum or elsewhere.

“Difficult” allows us to dismiss and avoid -- to further marginalize those who surface identity by labeling them myopic or as promoting identity politics. Yet all course content reflects identity politics. (Grant, 2020)

Do politics belong in the classroom at all, or should schools be safe havens from never-ending partisan battles? Can teachers use controversial issues as learning opportunities, and, if so, to teach what? And then, the really sticky question: Should teachers share with students their own political viewpoints and opinions?

In their book, The Political Classroom: Evidence and Ethics in Democratic Education, Diana E. Hess and Paula McAvoy offer guidelines to these and other questions, using a study they conducted from 2005 to 2009. It involved 21 teachers in 35 schools and their 1,001 students. Hess is the dean of the school of education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and McAvoy is the program director at UW-Madison's Center for Ethics and Education.

Schools, they conclude, are and ought to be political places — but not partisan ones. I talked with them recently about how, in today's highly polarized society, teachers can walk that very fine line. (Drummond, 2015)

On average, conservative cities own a 26-point gap in black-white math scores, and a 27-point gap for reading — still nowhere near ideal outcomes, but roughly 15 points and 13 points lower, respectively, than what we see in progressive cities.

The embarrassingly inequitable outcomes in progressive cities should ignite the residents of those cities to demand education systems that work equally well for every child, not just because their values demand it, or because the success of the city depends on it, but because addressing it is critical for the children in their cities.

In the book Blindspot, the authors reveal hidden biases based on their experience with the Implicit Association Test. Project Implicit is graciously hosting electronic versions of Blindspot’s IATs. These should work properly on any desktop computer and on several touch-screen devices including iPads, Android tablets, Nook tablets, and the Kindle Fire.

While the list below doesn’t characterize every school in America, some common paradigms dominant in our system include:

Deep and persistent disparities in achievement based upon race and class

Disproportionate discipline and special education placements for children of color

Emphasis on control and compliance

Excessive reliance on pressure and fear of failure as motivators

An impersonal and often punitive school culture

Learning is often characterized by covering material, not enough deep engagement, curiosity, stimulation

Take a moment to reflect: Does this accurately describe your school or district? The downside of this paradigm is that it does not lead to better learning outcomes. It simply isn’t working for a majority of our students.

Can schools instead be places where:

- A child’s race or economic status does not predict how well they will do in school?

The culture and language of children are treated as assets and resources to be valued rather than negated by assimilation?

Children are inspired, their curiosity is encouraged, and their dreams are fed?

Teachers feel appreciated and are able to teach with joy, passion and inspiration? (Noguera, 2020)

“You can’t have a school that’s not systemically racist in a society that is systemically racist. Schools are a part of the system. If society changes, it would happen in the school, but I don’t know that schools could change first and impact society. My mind can’t process it happening that way. Schools are a microcosm of the world. But there’s no way you can change the society without including changing in the schools where children are being educated.” (words of Aingkhu Ashemu, Graduated from Denver School of the Arts, 2017. Age 20.)

“I saw my high school as the mirror image of our nation, but I wondered how “inclusive” it truly was if classes pertaining to African history were occasionally offered as semester electives, as if Black students were an accessory to the administration’s vision. I want more for my country and the students who attend school after me.” (Words of Leah Hunter, Hume Fogg Academic Magnet High School, Nashville, TN, graduated 2020. Age 17)

Listen to students talk about differences and preferences based on skin color.

School climate surveys show too many students of color, English-learners, and students from low-income families say that school is not for them: they don’t feel safe in school or feel like they belong, and they aren’t asked to do challenging or interesting work.1&2 The COVID-19 pandemic is drawing attention to and exacerbating prior, inequitable conditions, introducing new challenges and new opportunities. An intentional policy stance that values culturally and linguistically responsive education (CLRE) is essential to addressing the inequities in expectations and opportunities that have been laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Teachers can teach hard history—and the present—and teach the ways that marginalized groups have always worked to honor their dignity and humanity. Teaching and exposing the realities of what is happening now may be very difficult for students, so balancing teaching the “hard stuff” with action or activism helps. Teachers can teach lessons that expose oppression and also teach lessons that are rooted in action, activism, care, joy and healing.

When crafting lessons and curricula—even now—I ask teachers to look for the holes, the gaps, the voices in the text that are silenced, the current events that can be transformed into powerful lessons that lead to critical thinking and action. What do we do, today, in the moments of pause and wonder and frustration when we can remember those who are, in fact, without? Those who we feel we are unable to reach from our homes, from our reclusive places and spaces. Where do we pair stories within the stories? (Pitts, 2020)

We must commit to teaching in a way that totally disrupts and dismantles the system of oppression we have been operating within for over 400 years.

We will change the narrative by:

Holding ourselves individually and mutually accountable: When you see something, say something. It does not matter if it is at your dinner table, the hallways of your school or on an outing with friends. We must combat racism by facing everyday bias head-on. Teaching Tolerance provides great resources to do just this. We can no longer be silent about the things that matter!

Ensuring representation is at the forefront: Look around your committee, your table, your office, your curriculum—who is there? Who is not there? Why? Challenge yourselves to ensure that the people not currently at the table are represented on your committee, in your images, and in your curriculum because representation matters!

Caring about more than ourselves: It does not matter if this is not personally impacting you. It should matter that Black people are still underpaid, mistreated, underrepresented. It should matter that Black men are so feared by police officers that a routine traffic stop can quickly turn into a death sentence. It should not matter if you have students of color or not, you still should care. (Wing, 2020)

To create equity in their schools, educators must seek to validate and acknowledge students, expose and reveal the unseen, encourage questioning, and facilitate reflection (Block, 2016)

For example, the Vermont Department of Education knows exactly how the reading skills of this year’s third graders compare to last year’s. It calculates how seventh graders from rural districts perform in social studies compared to their urban counterparts, and how the math skills of nonnative English learners measure up to those of native speakers.

Similarly, school districts routinely track their own stats, from the attendance record of students in the free and reduced price lunch program, to how much money they’re spending on books, travel and heating fuel.

Yet we can’t answer the most basic questions about Vermont schools: Who are our teachers and where do they come from? Why can’t we? Because no one has ever been assigned that “homework problem.” In many parts of the state, it’s not even in the lesson plan. (Picard, 2010)

The overt silencing of Black girls’ voices arises in the broader context of over-policing and police abuse. Even a science experiment by a Black high school student led to arrest and felony charges when a mixture of chemicals caused a small explosion, popping the top off of her water bottle. (The charges were later dismissed.)

Black girls make up just 16% of the female student population in the country, but account for more than one-third of all school-based arrests. A 2007 report in the journal Youth and Society found that Black girls were penalized for deviating from social norms of female behavior, and in particular for being “loud, defiant, and precocious.” Research from Georgetown Law’s Center on Poverty and Inequality has also found that, compared to white girls of the same age, Black girls are perceived as more adult and less in need of nurturing, protection, support, and comfort.

This document was published in 2016 and is a snapshot of the racial diversity of educators in elementary and secondary public schools. At the time, The U.S. Department of Education was dedicated to increasing the diversity of our educator workforce, recognizing that teachers and leaders of color play a critical role in ensuring equity in our education system. You can read the summary of the findings on page 9.

For Juneteenth 2020, I am challenging educators to emancipate themselves from this colonized curriculum that tells history solely through the lens of White people. For real change to happen in society, we have to change the way we are teaching our students, all students.

Unfortunately, with the social unrest and demands for justice after the murder of George Floyd, some educators only think they need to take action if they have Black students in their class or school. Even schools with no Black students need a liberated curriculum free from the grips of white supremacy and colonization. Those students may move to another city or town that is more diverse and become just like Amy Cooper—threatened by the presence of a Black man. All educators must be engaged in this work

- Addressing Inequity in Early Childhood Programs; Personal Experiences and Perspectives; Inequity in Early Childhood Education; Early Childhood Education Undervalued; Historical Traumas; Inequities in Policies and Practices; Promoting Equity in Early Childhood Programs

Research shows that having a teacher of color can help students of color reach better outcomes; but the benefits extend to all young people, preparing them to live and work in an increasingly diverse society.

What becomes possible when educators understand race and racism? This question guided an expert panel of public and private school teachers and administrators assembled recently by the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education. The panel was part of a day-long summit to build racial and cultural competency among educators. (Anderson, 2014)